Our new Spanish voice engine is the next step in bilingual-friendly voice AI for kids

September 25, 2023

Introduction

A young girl who speaks Spanish at home and English at school is asked to translate for her parents around town. She is required to switch between the two languages, depending on the social context and is asked to develop interpersonal skills beyond her age. Yet she’s often judged for having an accent in both languages.

A boy grows up speaking mostly English and Spanish at home. At school he’s only allowed to speak English. He pushes himself to speak Spanish with his grandmother, embarrassed by the rift between his identity and the language he feels he’s supposed to speak perfectly.

Bilingual kids are often asked to bifurcate their identities and their languages, and their success is often predicated in schools by their ability to do so. Not only do they continue to be misdiagnosed for language development issues, but treated monolingually in a language that is not spoken at home, such as English, they risk falling behind in literacy. This is where a voice engine, like the one we’ve developed here at SoapBox, has a role to play.

SoapBox’s voice engine has been helping teachers and parents measure a child’s phonemic awareness and development in English for several years. These measurements directly impact a child’s literacy development and help diagnose early speech-sound disorders. Now, with new funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation we’re building this engine for Spanish as well. Spanish is the second most spoken language in the US overall and the most spoken language among English learners in US schools. For SoapBox, this Spanish engine is the next step in delivering equitable speech tech, as it will allow more kids to be assessed in the language they use at home.

In order to mitigate bias in speech recognition, we must first ask, what is a “valid” way to speak, and who gets to decide? The process starts with diverse training data. The data you feed the model is the language you legitimize, because the people who speak that language will be able to use your technology more effectively than others. SoapBox already commits to incorporating a range of dialects in an effort to mitigate bias. Developing a Spanish language voice engine, allows us to extend our mission to make the voice AI as equitable as possible.

Another example of where it’s important to be able to assess a child in the language they speak at home is in relation to early dyslexia screening. In RAN (rapid automatized naming) tests, a child might be asked to name what they see as quickly as possible. Language specific vocabulary is not what’s being measured here, so giving kids the option to respond in their dominant language yields more prompt responses and more accurate results. And, as a result, less false positives in dyslexia screenings.

While the foundation of speech recognition software is monolingual; that is, it expects people to be speaking one language at a time, the SoapBox voice engine has been built with the flexibility to incorporate Spanish words and phrases, as custom words for example. That said, processing of bilingual data by most automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems is still found to be unreliable.

What do we mean when we say bilingual data? A popular example is code-switching. An example of phrase-level code-switching is the sentence “Tengo que caminar a escuela pero it’s raining so hard!”

Code-switching can happen at different linguistic levels, for instance at the word level (single word inserts), or at the grammatical level (ex: adding a Spanish verb stem to an English verb). Bilingual speech also means phonemic flexibility; pronunciations that are distinct for monolinguals are continuous and interchangeable for bilinguals. Training data that reflects these features will go a long way to mitigating bias in voice technology. On a larger scale, this can help support the status of bilingual speech that is often invalidated or unacknowledged. SoapBox technology in English and Spanish will support bilingual learners by allowing custom words that cover colloquial pronunciations, and enabling custom language modeling that covers any variety of language structure.

To better understand the importance of this in voice AI, let’s first dispel some myths…

Myth 1: A bilingual is two monolinguals in one

A common misconception is that bilinguals are equally proficient in both of their languages, or have a UN-interpreter capacity to translate between them, or to read, write, and speak fluently across contexts. The premise of this is a misunderstanding of how language, culture, and society interact. That is, people often use and learn different languages in different contexts. A basic example is speaking one language at home and another at school; this can separate language use into two domains where, for instance, kitchen words are in the home language and academic words are in the school language.

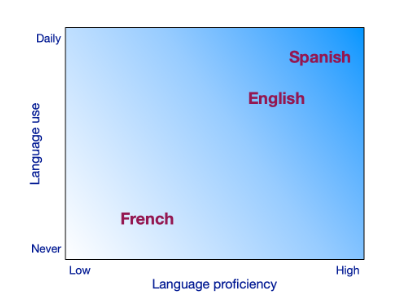

So, bilinguals aren’t two monolinguals in one brain. Instead, they have a multidimensional linguistic repertoire. The Bilingual Dominance Scale, pictured below, approaches the idea of language dominance through a combination of use and proficiency.

The Listening Bilingual (Grosjean and Byers-Heinlein)

People frequently switch between “language modes,” when they only activate certain languages to communicate. This creates the illusion that they’re two monolinguals in one. However, assessing kids this way lets them fall through the cracks and isn’t reflective of how bilinguals communicate with each other.

Assuming that a child is equally dominant in both languages–and thus treating their two language selves as distinct–can remove their ability to fully express themselves. Not only that, but measuring a child monolingually is simply inaccurate.

Language modes are also harmful because they’re imposed systemically. Let’s take the case where a child in the US speaks Spanish and English at home, but only English in school. The child is learning that it is their job, as a minority or heritage language speaker, to accommodate for the dominant language and culture. The implications go beyond this child learning how and when to mode-switch — languages remaining inactive because of forced modes related to loss of heritage languages.

Myth 2: Code-switching as malpractice

When people say that code-switching muddies a “purer” form of language they are reinforcing a lot of misconceptions around how language functions. The first points to the keystone of descriptive linguistics: language is alive, evolving, and simply works how people use it.

To that end, even everyday monolingual language includes borrowed words – words that come from other languages and have integrated into the one you’re speaking. At one point, though, these would have been instances of code-switching. There are many culinary examples: English didn’t use to have a separate word for cow-that-is-the-animal and cow-that-is-the-meat; the word beef was borrowed from the Normans.

What code-switching naysayers should understand is that language is systematic and so is its evolution. Dialectal changes emerge and pattern out, sifting through social circles and observing or creating various linguistic restraints.

Without getting too much into the weeds, an example is how many code-switches happen around a trigger word, or a linguistic pivot that allows someone to switch languages within a sentence. Examples of these in Spanglish could be pero, like, but, and, as shown in the example from the beginning:

“Tengo que caminar a escuela pero it’s raining so hard!” or, alternatively,

“My brother me llamó ayer because he needed advice,” a sentence which syntactically respects both Spanish and English.

The term translanguaging describes bilingual speech as a person engaging fluidly with their entire linguistic repertoire and combined identities. This moves away from the implied separateness of the term code-switching. There is a wealth of research that shows how bilinguals use code-switching and translanguaging to communicate and connect. For instance, using the same mix of languages can be a way for two kids to highlight that they share intercultural identities.

Myth 3: Bilingualism hinders (language) development

There’s a lot to unpack here. One common fear is that children will confuse their languages. Another is that early bilingualism hinders a child’s linguistic or cognitive development. On the contrary, bilingualism has been proven to be beneficial in many ways, and infant brains are naturally equipped to handle multiple languages. Because languages may be acquired in different contexts, not all vocabulary in a single language might match that of a monolingual child, but the number of conceptual mappings has been proven to be the same.

When it comes to voice AI and early speech-sound diagnoses, it becomes more about phonemic differences and making appropriate goals.

In Spanish, only /s/, /n/, /r/, /l/ and /d/ exist in final positions. Because of this, certain tests may flag final consonant deletion as a common error for sounds not in this list. However, for a young bilingual child this isn’t necessarily an issue. In fact, it makes sense as they continue to develop phonetic distinctions between their languages. A bilingually-trained voice engine can help support these complexities, provide more accurate scoring information, and ultimately better support the child.

The way around this? The ideal solution would be to develop curricula and methodologies that destigmatize code-switching and create spaces for children to participate in bilingual mode. Incorporating voice technology that works in both Spanish and English, such as the SoapBox voice solutions, will be a step change for emerging bilingual learners.

Dubbed “The Language Combination Affect,” researchers Leah Fabiano-Smith, Chelsea Privette and Lingling An have found that assessing kids using a combination of their languages proves most effective in diagnosing early speech progression and potential disorders. Forcing a mode might handicap a bilingual child, especially when language-specificity is not what’s being measured.

Conclusion

So, starting to introduce tools and digital speech solutions, such as the SoapBox Spanish voice engine, that enable students to switch between Spanish and English in their daily life at school is already a fundamental step towards fostering inclusiveness.

At SoapBox, we recognize that translanguaging and the use of bilingual phonetic data can help prevent misdiagnosis and better support literacy development, and we will continue to develop our research and testing in this area. Furthermore, legitimizing bilingualism in technology will support its status overall, accurately respond to more children’s speech, and help set them up for success.

Author: Sela Dombrower, Computational Linguist / NLP Engineer